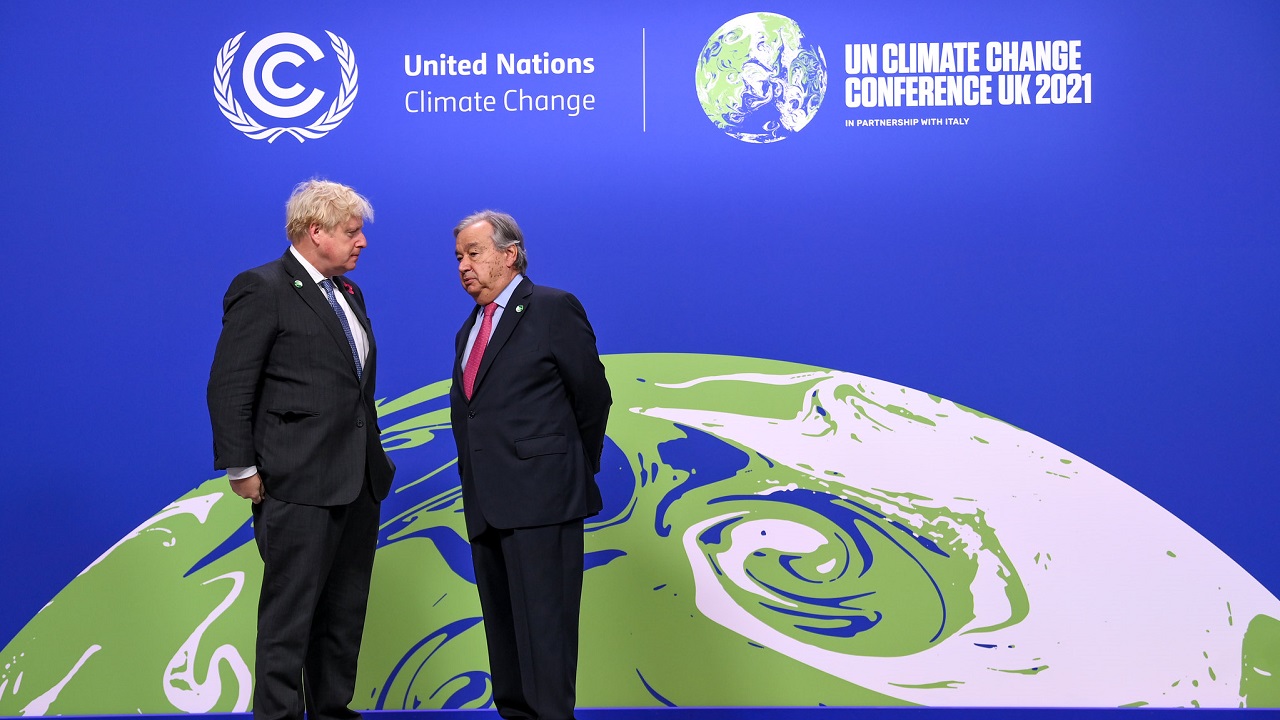

Delegates attend the Exploring Loss and Damage event at Cop26 on 8 November 2021. Photograph: Justin Goff/ UK Government, Flickr.

If ever a COP were burdened by high expectations, it was Glasgow COP 26. In the face of a rapidly depleting carbon budget, escalating scientific warnings, and a run of alarming weather extremes, COP 26 was billed as “literally the last chance saloon”. At the same time, the wider context to the Conference was decidedly inauspicious. The formal UNFCCC climate negotiations had been on ice for two years due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which had wrought devastation across the world. The continuing health situation had raised immense obstacles to the smooth organisation of the COP, to the point of uncertainty over whether it would be held in person at all. Relations between China and the US were at a low ebb, with wider diplomatic tensions also engulfing the UK host and others. As COP opened, it was hard to see how the gap between high expectation and gloomy reality might be bridged. In the event, COP was neither the fiasco that some had feared, nor the decisive turning point that others had hoped for. There were some significant wins and pleasant surprises, but also many disappointments and frustrations; in this sense, the “extraordinary COP in extraordinary times” resembled many other COPs. But looking beyond the specific substantive outcomes, what do events in Glasgow tell us about the wider politics of climate change, and how these might play out in this “decisive decade”? This blog post builds on two others that I posted around COP 26, one on its eve, the other halfway through. Aside from some excess pessimism, the points I made in those earlier posts still stand.

A positive reset

Glasgow marked a surprisingly positive reset of intergovernmental efforts to combat climate change under the UNFCCC process. To recall, COP 25 in Madrid in 2019 had been marred by unconstructive squabbling, stymying the adoption of the Paris rulebook and anything resembling a strong cover decision. COP was, of course, then cancelled in 2020. Fractious virtual discussions held in June 2021 pointed to difficulties ahead when formal negotiations resumed. In the event, however, and notwithstanding the aggravations of Covid restrictions, the atmosphere in Glasgow was remarkably upbeat. This point should not be overstated: delegations fought their corner vigorously, strong words were exchanged, and emotions ran high, especially towards the finale. But by and large, this was a constructive and good-tempered COP. There was a sense that delegations were mostly getting on with the job, with less of the political game playing and gratuitous objection that can plague the process. Perhaps the delegates were simply pleased to see each other, and weary of the politicking from Madrid. After all, negotiations are about people, as much as politics. Aside from personal relationships, it was evident that delegates had instructions from their capitals to set aside wider differences, and “carve out” space for constructive deliberations on climate change. Perhaps the stark warnings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which had just released its sixth assessment report on climate science, had focused minds.

The USA: “back in,” but the damage is done

Another contribution to this relative bonhomie was no doubt the presence of a supportive US delegation, flexing its diplomatic muscles in favour of the process. One of the few silver linings of the devastating Covid-19 pandemic must surely be the postponement of COP 26, which would otherwise have taken place not only under a hostile Trump Presidency, but in the midst of a messy interregnum, which would have both tied the hands of the US delegation and diverted media attention. Substantive US positions on such issues as climate finance and support for loss and damage were disappointing to developing countries. But in terms of political and diplomatic effort, there was a world of difference from the last three COPs, when President Trump had been in charge. Completion of the Paris rulebook and adoption of the unexpectedly ambitious Glasgow Climate Pact can be attributed in no small part to diplomatic cajoling and manoeuvring on the part of the US. If nothing else, the obstructionists in Madrid - Australia, Brazil, Saudi Arabia - simply had less room to press their agendas without a sympathetic fellow populist in power. The value of US diplomacy under President Joe Biden was also reflected in the numerous significant bilateral and multilateral deals that were announced on the side of the formal negotiations: from methane to green steel to bespoke financing arrangements to help South Africa accelerate its transition away from coal. And it is not just practical diplomacy, but also equity, reciprocity and “taking the lead” that matters. Would so many nations have declared for net zero, had the US not done so in April 2021? It would be unbalanced and unfair for such countries with tiny per capita emissions as India, Viet Nam, Nigeria and Nepal, to pledge net zero, without the world’s largest historical, second largest current, and outsized per capita, emitter doing so first.

But the fact that the US “is back” under President Biden, and is belatedly making some long overdue positive moves, cannot redress the immense harm done to the UNFCCC process by this carbon superpower over the past three decades. The four-year hiatus under Trump was not so much an embarrassing aberration, but rather the continuation of a pattern: the damage and delay to climate multilateralism caused by Trump compounded eight lost years under President George W. Bush, who walked away from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol - with its legally binding emission targets that had been carefully negotiated by the Clinton Administration – while failing to implement any serious domestic climate legislation. The Kyoto Protocol nevertheless came into force and climate policy progressed with real impact, especially in the EU. But absent the US, there was zero chance of persuading the large emerging developing country emitters to pursue a low carbon development path, in parallel with their push for economic growth and poverty alleviation. And so global emissions rose to the dangerous levels we see today. Had the US remained engaged in the climate regime in the early 2000s and fulfilled (even partially) the leadership role incumbent on it, as the world’s largest historical emitter, economy and technological superpower, we might be in a very different place today. Unfortunately, even if one decides to charitably forget the past, there can be little confidence that the current more engaged stance of the US will survive the next change in Presidential administration, or even the mid-term congressional elections.

China: unfairly maligned

And yet, the Northern media and political elites tend to cast China and India in the role of villains, rather than the US. This was abundantly clear in the coverage of COP 26, notably in the commotion surrounding the “coal fight” of the last day, which saw the phrase “phase out” replaced by “phase down” (more on that below). In the run-up to Glasgow, much of the attention was focussed on China: would President Xi Jinping attend? Would China declare a more ambitious target? And when neither happened, China was criticised for absenteeism and inflexibility. But these were the wrong questions to ask: it didn’t really matter whether President Xi was physically present or not, and China had already announced its climate plans to the UN General Assembly in September 2020, including its ground-breaking 2060 net zero target. Expecting another significant announcement so soon after that was unrealistic. What really mattered was China’s overall approach to the negotiations; the extent to which it would display a constructive and ambitious stance, which would enable the adoption of the overdue Paris rulebook and a strong cover decision. In the event, the more conciliatory atmosphere within the COP also rubbed off on the Chinese delegation, which agreed to language ruled out two years ago in Madrid. All the furore over phase-down vs phase-out has obscured the major concessions on the part of China reflected in the Glasgow Climate Pact: a stronger emphasis on 1.5˚C than in the Paris Agreement; reference to “net zero” “by or around mid-century” (a much more direct reference than in the Paris Agreement); a request for parties “to revisit and strengthen” their 2030 targets next year (initially dismissed as a rewriting of the Paris Agreement); and mention of coal. China also eventually compromised on common timeframes and reporting rules, important components of the Paris rulebook. This is not the behaviour of an intransigent country. China has travelled a long way in its understanding of, and response to, climate change over the past 30 years, charting consistent (if insufficient) progress at home and abroad, in contrast with the toxic “flipflopping”, and ultimately woefully inadequate response, of the US.

But arguing over who is the biggest climate change villain is not helpful. What is clear is that, with around 40% of the world’s emissions between them, both China and the US need to do much more if humanity is to be saved from dangerous warming. The US might have a lot of catching up to do, but equally China can no longer shirk the responsibility that comes with its present level of technological and economic development, not to mention per capita emissions now well above the world average.

In this respect, one of the more promising outcomes of Glasgow was the announcement that China and the US have resumed the constructive dialogue and diplomacy that proved so critical to forging the 2015 Paris Agreement. On Wednesday of week two, there was a (pleasant) sense of déjà vu among climate veterans, as US climate envoy John Kerry and China’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua issued a joint declaration, signalling the two countries’ commitment to practical and diplomatic cooperation on climate change, despite their major differences on almost all other issues on the international agenda. The content of the joint declaration proved to be decisive, with China insisting on replicating the bilaterally agreed language on coal (“phase-down”) in the Glasgow Climate Pact. Given that China had just committed to this term – and is known to take these declarations very seriously – it is baffling that the UK COP Presidency and the US thought that the alternative “phase-out” might be acceptable. But of far greater practical significance is the hopeful message conveyed by the declaration: that tackling climate change is a unifying topic for the two superpowers, rather than a divisive one. After the turmoil of the past few years, this could not be taken for granted. The world should breathe a sigh of relief that it is the case.

India: moving centre stage

COPs can be dramatic events and COP 26 was no exception. There were many theatrical performances, not least impassioned interventions from the typically charismatic leaders of small island states. However, it was India who “stole the show” in Glasgow, bookending the Conference with spectacular interventions at its start and close; not so much in terms of oratory, but more in terms of concrete outcomes. On the first day of the Leader’s Summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised the world – and apparently much of the political elite back home – by announcing that India would pursue a net zero target by 2070, accompanied by 2030 milestones on carbon intensity, renewable power, and emission cuts. While short on detail, this declaration amounts to a huge turnaround for India, which had up to now resisted the pressure (mostly from the UK and US) to set a net zero target. Throughout the 30 years of the climate regime, India has resolutely championed equity, pointing to unsustainable lifestyles and excessive consumption in the North as a major contributor to the problem. The country’s tiny per capita emissions – still less than half the world average and 1/8 those of the US – provide it with a compelling moral platform for doing so.

India again took centre stage in the dying hours of COP 26, with its Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav calling for changes to paragraph 37 of the draft Glasgow Climate Pact. The offending language called for “the phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, recognizing the need for support towards a just transition.” China, South Africa and Nigeria also rejected the phrase, but it was India’s more elaborate statement invoking unsustainable lifestyles that captured the headline writers. Inexplicably, despite having heard these objections, COP President Alok Sharma declared, at the close of the informal plenary meeting (it was now Saturday afternoon), that any changes would unravel the entire deal, and that he intended to propose for adoption the decision as it stood. This was a bizarre move, given the consensus decision-making practice of the climate change negotiations combined with geopolitical realities: two small countries could perhaps have been overruled, but never China, India, South Africa and Nigeria. There ensued an hour or so of “huddle diplomacy” on the plenary floor, on the podium and in a side room. The upshot was a revised paragraph, which responded to the objections, but in doing so raised the ire of small island developing states and others, including Switzerland. The final text reads: “…accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition”.

Uncomfortable truths

India and China took most of the flak for the change from phase-out to phase-down of coal, which was widely perceived as a watering down (less attention was paid to the language on fossil fuel subsidies). Even Alok Sharma, who is supposed to remain neutral, claimed that “China and India will have to explain themselves and what they did to the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world”. This scapegoating is unfair, and obfuscates the important lessons behind the drama. China and India were not the only ones expressing concerns, and they had reason to do so. And while their interventions in the final plenary were highly visible, important changes to the original President’s proposal [1] insisted upon by others earlier in the week passed under the radar: the qualification of fossil fuel subsidies with “inefficient” and coal with “unabated” (both G20 language, and with “unabated” indispensable to the US [2]). Moreover, the final paragraph 37, despite all the changes from the much starker initial draft wording, still represents a breakthrough [3]. It may sound strange that documents of the climate change regime have never before mentioned coal and very rarely fossil fuel subsidies, but that is indeed the case, paying testimony to the success of fossil fuel interests in deflecting attention from the main causes of climate change. That silence was becoming increasingly untenable, however, and although it would be a stretch to say that coal has been “consigned to history” (an avowed “personal priority” of Alok Sharma in the run-up to COP), the tide is certainly turning, and paragraph 37 proves it.

The drama of that final day confirms the uncomfortable truth that, as elsewhere on the global agenda, the red lines of the great powers must ultimately win out. The Swiss Environment Minister complained bitterly about the “untransparent process” through which the final changes were made; but in fact, the process was transparent: the dance of the superpowers on the plenary floor was visible to anyone with an internet connection. While mask-wearing made it impossible to discern the words being spoken, it was not difficult to guess what was going on, as the UNFCCC public webcast camera skilfully zoomed in on the players and huddles that mattered [4]. The problem wasn’t transparency, it was realpolitik. The concerns of India and China had to prevail over the pleadings of small island states or even rich-but-small countries such as Switzerland. The regime may operate on the basis of one-country-one-voice, and this is vital in providing a platform for the vulnerable to speak as equals to the high emitters. But when it comes to the crunch, some countries matter more than others, China and India amongst them. Alok Sharma’s failure to recognise this could easily have propelled Glasgow toward the nightmare scenario of another Copenhagen.

Another uncomfortable truth revolves around the competing equity claims of the poorest and most vulnerable, in the context of a rapidly shrinking carbon budget. While coal burning and fossil fuel subsidies are aggravating the sea level rise and erratic weather that pose an existential threat to climate vulnerable communities, millions of the world’s poorest people rely on them for basic energy services and employment. Indian Environment Minister Yadav explained this well in his plenary intervention: in India, state subsidies to LPG have helped poor households move away from using biomass as a cooking fuel, reducing deadly indoor air pollution. In China, rural households in the North of the country are dependent on coal to heat their homes amid freezing winter temperatures. In South Africa, thousands depend on coalmines for their livelihoods, as well as basic energy access. Similar stories could be told across the developing world. Phasing out the subsidies and coal on which very poor communities depend will take time, and unfortunately, is at odds with the urgency to cut emissions that confronts the most vulnerable. But the fact that this dilemma exists at all – in effect pitting the interests of some of the poorest and most vulnerable against each other - is due to the massive and continuing over-consumption of the global carbon budget by the North, and indeed the prevarication of wealthy nations over phasing out their own coal and fossil fuel subsidies. The UK is still considering opening a new oil field and a new (metallurgical) coal mine, while Germany will only finally phase out coal in 2030. There have been intense debates in both these highly developed countries over the economic and social impacts of moving away from fossil fuels. How much more so for China, India, South Africa, Nigeria and others.

The EU: lacklustre

Among the other players, the EU was accused of a muted even lacklustre performance by many environmental NGOs and commentators, who were hoping that the bloc would take a more proactive, leadership role. The EU Commissioner Frans Timmermans delivered powerful plenary speeches about ambition and urgency, but this oratorical brilliance didn’t cross over into the substantive negotiations. While the EU has some of the most advanced climate policy in the world, it was nevertheless accused of foot dragging on climate finance, and generally failing to really take the lead or champion the interests of poorer countries on such agenda items as adaptation and loss and damage. It is interesting, for example, that the High Ambition Coalition – the iconic North-South group founded by the small island states and EU in Paris – never really made a splash in Glasgow. One of the problems for the EU and others may be that, in this era of national determination, high level commitments on mitigation and finance were extracted and announced in advance before the COP, rather than negotiated at it. There was therefore less to do, negotiate and lead at the COP itself.

Climate finance: a new negotiation phase is launched

This will now change, however, as the COP launches into a new, and unprecedented, negotiation process on money. So far, climate finance under the UNFCCC process has been pledged by countries on an ad hoc basis, according to what they feel able to disburse, rather than in relation to any identified bottom-up criteria or top-down need. This shifted a little in 2009, when developed countries committed to mobilizing US$100 billion a year by 2020, extended to 2025 as part of the Paris Agreement deal. But this sum was always somewhat arbitrary, not corresponding to any expert-based assessment of requirements. This contrasts, for example, with the situation under the Montreal Protocol on stratospheric ozone depletion. Parties to the ozone regime negotiate the replenishment of its Multilateral Fund triennially, based on a technical assessment provided by its Technology and Economics Assessment Panel (TEAP). An agreed “scale of contributions,” derived from wider UN practice, then defines the share that each party should pay. Nothing like this has ever been done under the UNFCCC process (except for the secretariat’s administrative programme budget). It is almost unthinkable that it could be transferred to the climate finance arena. And yet, following a landmark decision taken in Glasgow, “deliberations” have now been launched on a new “collective quantified goal on climate finance,” to be agreed in 2024. Added to this is the new “Glasgow dialogue” “to discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimize and address loss and damage”, which also concludes in 2024. Don’t be fooled by the harmonious sounding “deliberations” “dialogue” and “discuss”: these decisions have unleashed a new round of talks that will make Glasgow seem like the calm before the storm. Climate finance has always been the most acrimonious of topics in the UNFCCC process, even before actual sums were up for debate.

The North-South divide persists

There were certainly signs of the fireworks to come in this arena at COP 26. Climate finance in all its manifestations emerged as a dominant theme – something I did not initially anticipate - partly resulting from the news that the $100 billion by 2020 finance goal has almost certainly been missed (final figures lag a couple of years). The UK COP Presidency managed to soften the political sting somewhat before COP 26 by commissioning a “climate finance delivery plan” aimed at reaching the goal as soon as possible, hopefully by 2023. But the need for greater, more accessible, and better-quality financial support is one of the few issues on the climate agenda that still unites the 134-strong developing country Group of 77 and China. Another is indignation at broken financial promises from the North over the past 30 years. And so, COP 26 saw a retrenchment of the North-South divide that has characterised the climate change negotiations since their inception. No matter that the Paris Agreement erased the UNFCCC categories of Annex I (developed) and non-Annex I (developing) parties: when it comes to finance, the North-South divide is alive and well. Developing countries, in their various groupings and under the G-77, all fought fiercely for a major uplift in financial pledges and a dedicated loss and damage funding facility already in Glasgow.

These were always vain hopes: most of the large donors had already announced their headline financial pledges by the close of the Leader’s Summit, and would not revisit them so soon. There was some good news, notably for the Adaptation Fund, which raised a record US$ 356 million in new pledges. Importantly, this included a first-time contribution from the US, which had originally snubbed the Fund because of its institutional links to the Kyoto Protocol. Now that the Adaptation Fund also serves the Paris Agreement - and now that the US has rejoined at least that treaty - American purse strings have been loosened. Qatar also pledged a first-time contribution, pointing to an expanding donor base beyond the OECD. But the sums remain many orders of magnitude below what is needed and are for adaptation, not recovery from loss and damage occasioned by climate extremes. The possible creation of a dedicated loss and damage facility opens up a whole new ballgame, politically and financially, evoking scary visions of blank cheques and lawsuits for the traditional donors, who also tend to be high historical emitters. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s description of Scotland’s £2 million pledge for loss and damage as “an act of reparation” points to the profound issues of liability and responsibility that may finally rise to the surface, after decades of bubbling below. The fact that an open-ended negotiation process was launched on funding arrangements for loss and damage at all is an achievement. The more moderate among the small island states – who typically place pragmatism above ideology – recognised this, persuading the G-77 to accept the Glasgow Climate Pact for the progress it was, rather than rejecting it as too weak. If anyone thought that the UNFCCC process was now going to retreat from politicised negotiation into a more sedate and technical implementation mode, then they will be disappointed.

The growing complexity of climate politics

On other fronts, events in Glasgow revealed the growing intricacy of global climate change politics, as developments in an increasingly wide array of arenas – multilateral and bilateral – come to impact on the UNFCCC process. Prior language agreed in G-7 and G-20 declarations proved pivotal as the basis for the Glasgow Climate Pact. Ensuring environmentally effective interaction with CORSIA, the international aviation offset system, was a significant issue in finalising rules for new market mechanisms under Article 6. Mention in the Glasgow Climate Pact of IMF special drawing rights as a potential funding mechanism suggests a much more important role for the wider international financial architecture. The UN Secretary General’s announcement of a new initiative to scrutinize net zero claims (by non-state actors) confirms the UN system’s wider commitment to fostering strong climate action, going beyond mere exhortation (but always within the constraints of state sovereignty).

Another key development in this space was the rise of “climate clubs” or “coalitions of the willing”: sub-sets of Parties, sometimes including non-state actors, going beyond what might be termed the UNFCCC “baseline” to declare more ambitious action in specific sectors. While such clubs – typically launched in a blaze of publicity - are hardly a new phenomenon in the international arena, they seemed to acquire particular prominence in Glasgow. This was the product of a deliberate focus of the UK Presidency, which genuinely believed in the value of these clubs in pushing stronger action on the ground, while also not wanting to leave the (perception of) success in Glasgow to the vagaries of the formal negotiations. If the latter collapsed, or disappointed, at least there would be the sectoral club declarations to point to as victories. Fulfilment of Boris Johnson’s “coal, cash, cars, trees” agenda was largely dependent on the delivery of these “clubs” which, among others, included declarations on deforestation, agriculture and commodity trade, halting funding for overseas fossil fuel projects, boosting zero emission vehicles, and transitioning away from coal. The latter perhaps best exemplifies the purpose of clubs, with its stronger provisions – notably specified timeframes – going well beyond the globally-agreed consensus language in the Glasgow Climate Pact. Needless to say, neither China, India, South Africa nor Nigeria signed up.

All these clubs are to be welcomed, and have real potential to help move the needle, but only if robust follow-up mechanisms are put in place. The UK Presidency now has a heavy responsibility to ensure not only that existing signatories take their pledges seriously, but also that new members are encouraged to join. There must be a real reckoning of progress at COP 27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, with perhaps a passing of the baton to the Egyptian Presidency or the UNFCCC secretariat to continue the work. So far, although Alok Sharma has undertaken in general terms to push for greater ambition throughout the term of the UK Presidency to COP 27, nothing has been said about establishing durable mechanisms to monitor and advance the clubs.

Competing realities

So, what does all this say about the prospects for the global response to climate change? There are two competing realities here. One reality is cautiously optimistic. Glasgow has got the UNFCCC process back on track, after the washout in Madrid and the Covid pause. The Paris Agreement rulebook is finalised, the contours of the process for the next few years are clear, and there were tangible advances in the global narrative reflected in the Glasgow Climate Pact (1.5, net zero, scientific urgency, 2030, coal, fossil fuel subsidies). The Paris Agreement ratchet mechanism is starting to work, with the vast majority of countries having submitted NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution) updates, mostly stronger than the initial crop. The UNFCCC process has undoubtedly raised the global bar over the past three decades through a complex combination of norm-setting, peer pressure, learning, political visibility, reciprocity, mobilization of finance, project-based carbon markets and capacity building. Through these mechanisms and others, the laggards are clearly being pushed into doing more than they otherwise would, and those with the will but not the means are being helped to decarbonise and adapt.

But the competing, more pessimistic, reality points to a pace of progress that is far from commensurate with the urgent action required. The intergovernmental process is inherently slow moving and incremental, ill equipped for taking quick and radical decisions. Global negotiations inevitably prioritise forging consensus with constructive ambiguity, over finding the most effective solutions to the problem at hand. Those of us immersed in the UNFCC process who see great strides forward at COP 26 are right in our reality, but Greta Thunberg who dismisses it all as “blah blah blah” is correct in hers too. This clash of realities was perhaps best exemplified in Glasgow by governments speaking passionately of the climate emergency in plenary rooms, yet refusing to come out in favour of ending new oil and gas exploration, without which global temperatures will overshoot the 1.5˚C ceiling. And of course, it is very difficult to convincingly explain to the outside world how a single clause calling for the phase-down of coal can represent such a huge milestone after 30 years of talks.

How will these different realities play out, as the decisive decade unfolds? In times of such confusion, it can be instructive to turn to art and literature, and indeed these abounded at the Glasgow venue. For a thought-provoking vision of the future in contemporary literature, readers could do worse than refer to The Ministry for the Future, by Kim Stanley Robinson. In this novel, climate change is eventually turned around by a combination of UN diplomacy, the intervention of central banks, the scaling up of local low-carbon innovation, leadership by India, geoengineering at the poles, stratospheric aerosol injection, laws to protect future generations and the non-human world, a new global consciousness, radical disruption by covert guerrilla forces, mass rewilding of ecosystems, political change in Saudi Arabia, and, above all, real attention to the world’s injustices and inequalities. But even in his simplified fictional world, where Robinson could dictate a happy ending, it was a long, bumpy and messy process. It will be for our real world too.

Footnotes

[1] “Calls upon Parties to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels”.

[2] In plenary, John Kerry stated, no doubt with a domestic audience in mind: “we’re not talking about phasing out all [coal]. Not eliminating [coal]. Unabated”

[3] I am on record as stating in my blog post at the start of COP that “Even a sentence or two endorsing the end of coal in a political declaration would be a major step forwards” and in my follow up post halfway through the Conference, that mention of coal phase-out would be “unlikely to fly in the full COP”. I am glad to be proved wrong.

[4] Although this footage of the pause between plenaries has now been removed from the UNFCCC website.